Aetiology

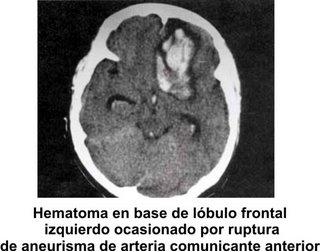

Primary: approximately half result from long standing hypertension

Secondary: neoplasm, vasculitis, bleeding disorder, prior embolic infarction, aneurysm, vascular malformation, trauma

Pathophysiology

- thought to be due to extravasation of blood from ruptured micro-aneurysms along walls of small intracerebral arterioles. These develop at sites of vascular branching where mechanical stress is maximal

- processes which result in aneurysm formation include lipohyalinosis and fibrinoid necrosis which weaken the walls of arterioles. Aneurysm formation enhanced by chronic hypertension

- alternative explanation for ICH that has been suggested is arteriole microdissection

- continued extravasation of blood results in formation of a haematoma with secondary development of cerebral oedema. May be resultant mass effect. PET data suggests that development of perihaematoma oedema may not be due to secondary brain ischaemia but may be due to reperfusion injury but other data (eg microdialysis data) suggests that it is due to ischaemia

- ± extension to ventricles

- early expansion of haematoma appears to occur from multiple small vessels in low blood flow area around the haematoma. Continued bleeding/re-bleeding is common

Clinical features

- onset usually during waking hours when patient is active

- abrupt onset

- progressive development of neurological deficit over minutes to hours. (cf. fluctuating or stepwise progression of deficit commonly seen in atherosclerotic infarcts, maximal deficit at onset in embolic strokes)

- prior TIA rare

- average age at onset 50-70 years (younger than in other types of stroke)

- ± lateralized headache

- vomiting common

- ± nuchal rigidity

- fits at onset in 17%. More common than in ischaemic stroke. More likely to occur if bleeding involves cerebral cortex

- 44-72% comatose by the time of presentation

Investigations

Specific symptoms

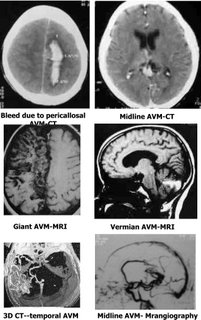

Tends to occur in certain locations: putamen (30-50%), subcortical white matter (15%), thalamus (10%), cerebellum (10%)

Putamenal

- due to bleeding from lenticulostriate vessel

- abrupt development of flaccid hemiplegia, hemisensory loss, homonymous hemianopia, paralysis of conjugate gaze to the side opposite the lesion and early alteration in level of consciousness. ± subcortical aphasia (dominant hemisphere) or hemineglect (non-dominant)

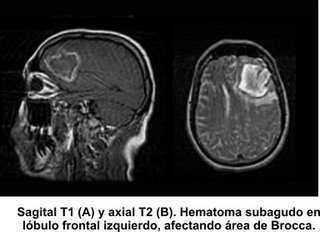

Lobar (subcortical white matter)

- less commonly related to BP than ICH in other locations

- signs and symptoms depend on anatomical site

- associated with higher incidence of seizures and headache at onset

- most common in parietal and occipital lobes

- lowest mortality and best prognosis for good functional recovery

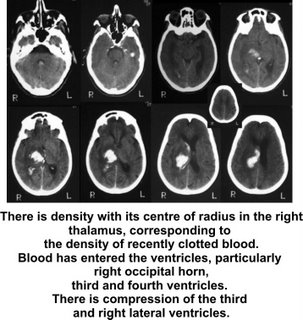

Thalamic

- unilateral sensorimotor deficit

- sensory signs predominate

- ± downward deviation of eyes with impairment of vertical gaze and small sluggish or unreactive pupils (Parinaud’s syndrome): due to downward pressure on vertical gaze centre in midbrain tectum

- aphasia or apraxia depending on side of ICH

- ± forced conjugate deviation of eyes

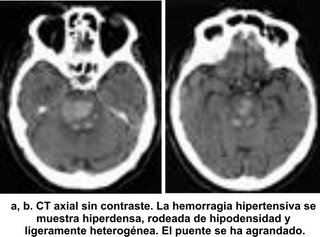

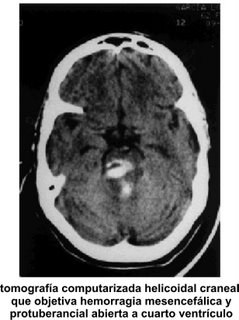

Pontine

- rapid onset of coma, quadriplegia, brainstem dysfunction and small unreactive pupils

- almost always extends into 4th ventricle

- high mortality

- almost always arises from paramedian branch of basilar artery. Cases of unilateral pontine ICH have a less dismal outcome

Cerebellar

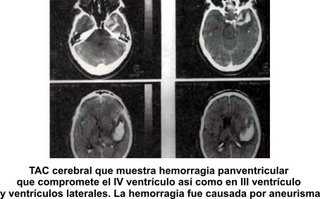

(CT scan)

- alteration of consciousness is unusual at onset but progressive deterioration is typical

- majority of patients will initially have 2 of following: gait, truncal or limb ataxia; LMN VII lesion, ipsilateral gaze palsy

- other common presenting signs and symptoms: nausea, vomiting, vertigo, nystagmus

Treatment

Medical

- control hypertension to minimize risk of further bleeding but risk of causing cerebral ischaemia as autoregulation is impaired. Some recommend aiming for systolic BP of 110-160 mmHg while others suggest that treatment should only be instituted if systolic BP in acute phase of ICH is >200 mmHg. Decrease BP slowly. b blockers are agents of choice with diuretics being second choice. Ca blockers, nitroprusside and hydralazine should be avoided as vasodilatation may lead to increased cerebral oedema and intracranial pressure

- management of intracranial hypertension

- anticonvulsants not routinely required. Haemorrhage into cortex predisposes to fits. Fits have been seen following haemorrhage into caudate but not putamenal or thalamic bleeds

- recombinant factor VII currently being studied as a means of reducing rebleeding but there is a risk that it may increase secondary damage if the perihaematoma oedema is due to ischaemia

Surgery

- cerebellar ICH >3 cm or in smaller lesions with clinical progression because cerebellar haemorrhage causes death in up to 60%. Surgical mortality is greatly reduced if the patient is still awake before operation: therefore early intervention is indicated

- ± lobar haemorrhage in patients who continue to deteriorate

- surgery for putamenal haemorrhage is controversial

- inappropriate for thalamic and pontine haemorrhages

- shunt for acute hydrocephalus

Prognosis

The prognosis of primary pontine haemorrhage was previously reported to be very poor, but the use of CT scanning has allowed the detection of small pontine haemorrhages that would previously not be detected

A case series of 26 patients suggests that prognosis is related to

- size of the haematoma

- level of consciousness

- pupillary abnormalities.

Patients with a poor prognosis became comatose within 2 hours of onset, their pupils were dilated bilaterally, pin-point or anisocoric and the transverse diameter of the haematoma was over 20 mm.

These findings are similar to the findings from a series of 32 brainstem haemorrhages, except with respect to the size of the haematoma. The patients were divided into 3 groups on the basis of eventual outcome. Approximately 1/3 died within 1 month, 1/3 were severely disabled (most were alert, quadiplegic and communicated only with great difficulty) and 1/3 had only minimal neurological disability. Good prognosis was associated with alertness or only slight disturbance of consciousness, normal respiration, positive light reflex, normal heart rate and haematoma <2.5>